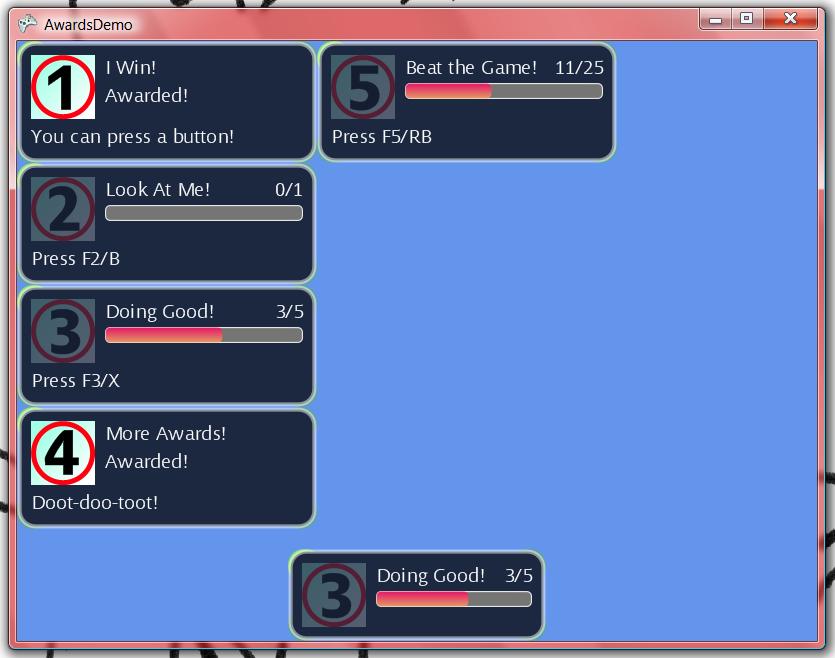

In Part 1 Nick Gravelyn introduced a simple framework for displaying award notifications in an XNA game. In Part 2 Daniel Hanson improves upon the award notifications adding in simple progress notification support and simple support for multiple gamer profiles.

This article further improves upon the award notifications by better following some XNA best practices, making the notifications more configurable, more reusable, and more animated. The updated AwardsDemo application includes the full darcs source code repository of the changes with respect to the version presented in Part 2. This article will mostly follow the repository's changes in chronological order and you are welcome to follow along. [1] With basic source control skills you can even attempt to cherry-pick some or part of the changes made to get a customized version of the code.

(It is always a good idea to get into the habit of using a source control system that you trust, even on the smallest projects.)

Contents

Best Practice: Resource Strings

In the AwardsDemo for Parts 1 and 2 there were several strings that were left as constants at the top of source code files. This is an easily made faux pas that can easily come to haunt a project as it nears completion. It can be quite easy to forget where in a game's source code a particular phrase or text is located, making it harder to tune the output to its best and particularly making it much harder to translate the game into other languages.

Even if you don't plan on releasing your game in multiple languages, it is still handy to have all of your text in one place for easy changes. It's also simply a good habit to get into, should the case ever arise that you do want to release a multi-lingual game. Happily, Visual Studio does a lot of work to make the best practice in this case (and many similar cases) an easy habit to get into.

In XNA (and .NET as well) the place to store strings that may need changing or will need translation (localization) is a "Resource file". Many Visual Studio templates will add one for you and adding one to a project without one is just like adding any other source file.

When you add a resource file in a Visual Studio project it actually adds two files to your project. The first is the .resx file which is an XML file that will store all of the strings (and whatever other resource data you might need). The other is a .designer.cs file and is an auto-generated file that will change as you modify the .resx file. There aren't very many reasons to edit the designer file by hand. This designer file provides you a handy class with static properties for access to your resources, in a similar way to how you might use an enum in your code.

Using PlayerIndex Rather Than GamerTag

In Part 2 to differentiate between different players unlocking awards, GamerTag was chosen. This is an easy choice to use, but it can break in subtle ways. GamerTag is not guaranteed to be unique and local profiles can share tags. The general best practice is that you should only use the GamerTag for display and for storing information you should use something more appropriate.

PlayerIndex is a very appropriate choice for storing award progress information for multiple players in memory. Several of XNA's examples use PlayerIndex everywhere, so it shouldn't be too startling to see it here as well. PlayerIndex provides a few useful benefits: it will be used in the revised notifications (which is discussed later in this article) and it should make more obvious the workflows that should be used with the awards component.

- When a player signs in (ie, in response to SignedInGamer.SignedIn), load the player's stored progress information (if there is any).

- When a player signs out (ie, in response to SignedInGamer.SignedOut), save the player's award progress as necessary and then clear all of the progress information for that PlayerIndex.

Using PlayerIndex in this fashion should make it more obvious that the awards component should not be storing more progress data than there are currently active players. It should also make it more obvious that the progress information should probably be stored in the appropriate per-user storage areas.

More Power to the Notifications

In Part 1 and Part 2 all of the drawing code was in AwardsComponent. While this is certainly a valid way to do it, it also has a certain inflexibility should one wish to customize the way notifications are drawn, or to reuse the notification drawing code to draw other interesting screens for awards.

For in game awards it is often useful to provide a screen listing all of the possible awards and their progress for that player. In Part 2, Gears of War 2 is cited as an example of a best-in-class game for in-game award displays and Gears of War 2 is a good example here as well: in between games, players can examine their progress in the "war journal" which displays awards in much the same way that the in-action notifications do. It makes a lot of sense to make the drawing code for awards amenable to just this sort of reuse.

To this aim, the drawing code was moved into two new classes: AwardDisplay and AwardNotification. AwardDisplay is meant to be a configurable display of an Award. AwardNotification is a subclass of AwardDisplay that configures the output to be the most useful for in-game notifications. AwardDisplay can also be customized in many ways without subclassing it, using the various properties that it exposes. The updated demo uses AwardDisplay customized in this fashion to provide the hints of how to unlock the awards.

AwardDisplay follows a relatively simple pattern:

public virtual void Update(GameTime gt);

public virtual void Render(SpriteBatch batch);

The Update method is expected to be called in an appropriate place during your game's Update and takes a GameTime object so that any animation it needs to perform can be correctly timed. AwardDisplay itself doesn't actually have any animation, but it is still provided so that subclasses can use it. (That is also the reason that both methods are marked virtual so that subclasses can override them to do things like further customized rendering or animation.) The Render method is then the one used during the game's Draw. It is named Render to distinguish that it renders to a given SpriteBatch rather than handling every aspect of the drawing. By accepting the SpriteBatch as an argument, it gives you the freedom to prime the SpriteBatch in whichever ways that you need to prepare it for particular layering, alpha blending, or other needs that your game may have.

In breaking out AwardDisplay from AwardsComponent two more useful information properties were added to Award that are useful to display to players: Award.Hint and Award.Description. These two fields come directly from the Xbox's Achievement menu: Award.Hint is shown when the award is locked to provide a hint to a player on how to unlock it. Award.Description is then the text shown when a player has unlocked the award and can reveal how an award was rewarded, some pithy expression about the award, or anything else that might be interesting to a player that unlocked the reward. (AwardDisplay displays both with the same property, AwardDisplay.ShowDescription, and determines automatically which string to use based upon the current award progress.)

AwardDisplay also takes into account the PlayerIndex when rendering an award. This can be important in multiplayer games so that players can tell at a glance which player a notification refers to. The notifications on the Xbox 360 all use the "ring of light" to mark which player(s) a notification is for. The updated notification backgrounds included in the demo provide a subtle PlayerIndex marker based upon the "ring of light". Notice the subtle green glow in the upper-left corner (PlayerIndex.One) here:

Using Bars to Assess Progress

Part 2 added the concept of partial progress to awards and provided counters to display that progress information. Progress bars are important ways to provide that sort of progress information at a glance and also happen to use a few techniques that are good to learn in XNA and often become relatively common patterns. So common, in fact, that the progress bar code in the updated demo is a good microcosm to explore the updated rendering code, and once the progress bar portions of it are well understood the rest should follow.

The progress bars make use of two textures, a back and a fill texture which are expected to be of the same size. The AwardDisplay class has a set of constants based upon the texture size:

// The height/width (square) of the progress bar textures

const int ProgressBarSize = 16;

// The width of the left/right edge for the progress bar

const int ProgressBarEdgeWidth = 5;

// The width of the stretchy middle for the progress bar

const int ProgressBarMidWidth = ProgressBarSize - 2 * ProgressBarEdgeWidth;

The texture this version of the demo uses for progress bars are both 16 pixels by 16 pixels square. The textures are split horizontally into three sections: the left end cap, the right end cap and a middle portion that will be stretched to appropriately fill an AwardDisplay. (These constants assume that both end caps are the same size.) The ProgressBarMidWidth constant is intentionally written to show that the three constants are interrelated, even though the math that the compiler has to perform here is trivial (the mid-width here is 6 pixels).

Using these constants, source rectangles are defined:

// These source rectangles deconstruct the progress bar textures

readonly Rectangle pbarSourceLeft = new Rectangle(0, 0, ProgressBarEdgeWidth, ProgressBarSize);

readonly Rectangle pbarSourceMid = new Rectangle(ProgressBarEdgeWidth, 0, ProgressBarMidWidth, ProgressBarSize);

readonly Rectangle pbarSourceRight = new Rectangle(ProgressBarEdgeWidth + ProgressBarMidWidth, 0,

ProgressBarEdgeWidth, ProgressBarSize);

Source rectangles are passed to a SpriteBatch to chop the textures into segments. These source rectangles are used in conjunction with destination rectangles to easily handle several forms of scaling and stretching of parts of a texture. Source rectangles refer to the coordinates of the source texture and destination rectangles refer to the screen coordinates where the source rectangle will be displayed.

AwardDisplay.CalculateProgressBar (called by AwardDisplay.Update when appropriate) calculates the various destination rectangles for the six source regions of the progress bar: left, middle, and right for both the background and the fill textures. The background destination rectangles are built to fill the entire region available for the progress bar. The fill rectangle is sized to represent the current percentage of progress unlocked. The important line here is:

// This is the amount of the progress bar that is filled.

float progfilled = MathHelper.Lerp(0, progwidth, Progress.Percentage);

This uses MathHelper.Lerp to calculate the amount of space that the progress bar should show as filled. MathHelper is a useful swiss-army knife than can be useful in many situations. Lerp is a shorthand name, used often in game and graphics programming, for linear interpolation. Given a range and a float between zero and one, Lerp returns a value in the range that corresponds to the float's position on an imaginary line. Lerp is one of a handful of functions in MathHelper that expect a float between zero and one. The easiest way to think of this range is that of a percentage: percentages are properly between 0% and 100% and easily expressed as decimals (floats) between zero and one. Based upon the progress percentage Lerp returns a value between zero and our total available space for the progress bar (progwidth), which is all that is needed to determine the amount of that space that should be filled for the progress bar.

One good resource on the reasons why these functions are normalized to work with floats from zero to one can be found in Shawn Hargreaves' post on the importance of curves in relation to transition effects and the game state management samples. Some of the same techniques can be used to experiment with the transitions employed in the AwardNotification class.

Animating the Notification

AwardNotification is a subclass of AwardDisplay specifically for use in the notification popups presented by AwardsComponent. Since AwardDisplay takes care of all the important stuff for drawing award progress information to the screen, AwardNotification can focus on timing how long the notification lasts. In addition, AwardNotification adds in simple animation during its transition on and then off the screen. AwardNotification also animates the progress bar for a notification.

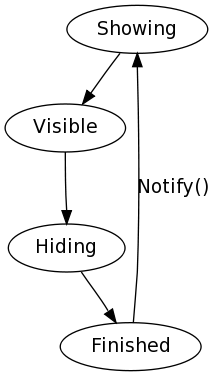

AwardNotification is a very simple state machine [2] which can be easily diagrammed [3]:

AwardNotification has four possible animation states, which are named and documented in the AwardNotification.State enum. Most of the states are simply timed: a progress float is incremented each frame based upon the elapsed time and the state's length TimeSpan. This float is kept between zero and one and is thus a percentage of time elapsed for that state. As mentioned earlier in this article, floats between zero and one, percentages, are quite useful and many functions are optimized to work with them.

The remaining state transition that isn't a simple timer happens when the method AwardNotification.Notify is called (as is marked in the diagram above). This method sets the AwardNotification up for a new animation. It also sets a few values that are used to animate the progress bar.

Animating the Progress Bar

The AwardsComponent enqueues notifications based upon Award.ProgressIncrement. As Part 2 points out, this is something that Gears of War 2 does in order to balance between too many notifications and not enough. What Part 2 does not point out is that Gears of War 2 also steadily animates the progress bar. In that game the notifications appear with the round increment, but then quickly "catch up" to any additional progress that is made. This is particularly useful on some of the notifications to let a player know to "keep doing what they are doing".

AwardNotification.Notify sets the starting progress to that round increment, but keeps track of that award's real progress information as well. During the "visible" state of AwardNotification the progress information is interpolated between the starting round interval and the current progress.

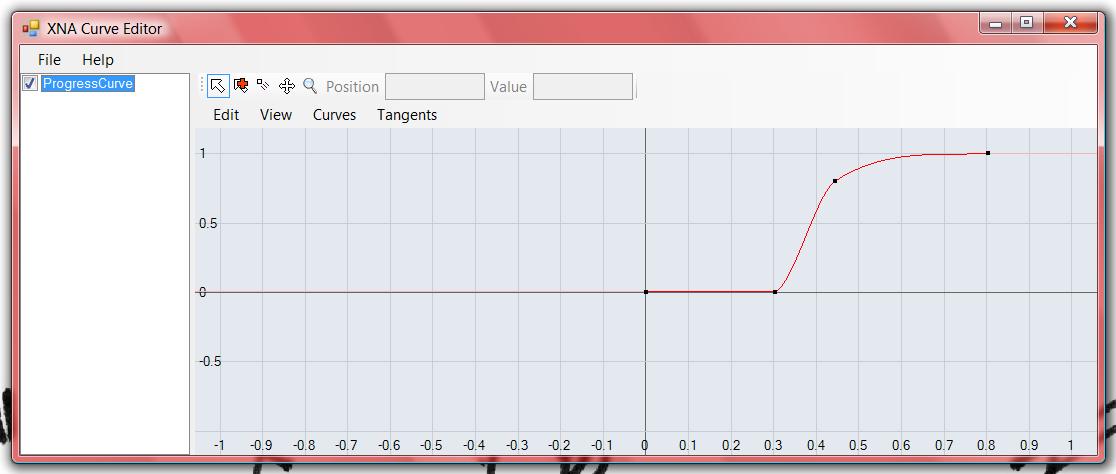

There are several interpolation techniques that could be used for this, including MathHelper.Lerp described above. In this case AwardNotification uses a manually-tweaked Curve file, created with the Curve Editor utility, called ProgressCurve.xml. A curve file is added into the content pipeline like the art assets and the Curve Editor is a useful visual tool for designing mathematical functions that can be used in any number of places in a game.

Here's what the ProgressCurve.xml looks like in the editor:

In the Curve Editor the x-axis can be thought of as the input range for the curve and the y-axis can be thought of as the output range for the curve. In this particular curve the range we are interested in is between zero and one: the input is to be the state's timer percentage. The output that we are interested in is then another number between zero and one, which might be thought of as the "real progress percentage". As the curve nears 100% (1.0 on the y-axis) we get closer to whatever the player's true progress is.

In this case the idea was to highlight the round increment for a good period (the first 30% of the timer), quickly (but smoothly) ramp up to near-current progress (reaching nearly 80% of the current progress around 44% of the timer). The last 20% of the timer is then "real-time" showing 100% of the current progress information. It was tweaked several times in the Curve Editor to produce a final result that looked interesting when pushing the buttons quite quickly in the updated AwardsDemo.

Curves like this may seem complicated at first, but the Curve Editor is a powerful tool to get mathematical formulas in an easy to use visual fashion. Curves edited in this fashion can replace the simple curves offered in MathHelper like Lerp and SmoothStep. If curves are edited for the range between zero and one in both axes it is a simple matter to replace an instance of one of these built-in functions with a custom curve. Sticking to this range also makes it simple to chain curve evaluation with these built-in functions and even with other curve evaluations.

For example, the progress indication animation in AwardNotification began as simply a MathHelper.Lerp, but this did not seem interesting enough and the curve was created to make the animation more interesting, but it still uses the Lerp to convert from the curve's output range to the progress range.

Go Forth and Award Your Players

At this point the updated AwardDemo project is even more polished than in Parts 1 and 2. It is also arguably better at this point than the in-game notifications of many retail Xbox 360 games, albeit most of them exclusively rely on the 360's dashboard notifications. Xbox Live Indie Games don't get 360 achievements and thus don't get the 360's dashboard access to achievement progress screens and notifications. This project, taking some cues from Gears of War 2, which has some of the strongest in-game notifications and progress screens, hopefully provides a great tool for any Xbox Live indie game developer to have a good, polished-looking awards system for their games.

| [1] | Once you've installed darcs, you can get repositories with only the changes up until a chosen patch with darcs get AwardsDemo AwardsDemoNew --to-patch="Patch Name". Another good tool to use is darcs changes --interactive --reverse (--interactive can be abbreviated to -i), which walks you through one patch at a time. Typing 'n' will move you to the next patch in order, typing 'p' will show you the diff (changes) made by that patch in a nice pager, and typing 'x' will show just the files that were affected by that patch. Type 'q' to quit and '?' for more help. |

| [2] | State machines are very useful conceptual models for programming. There is much study available on the subject of state machines, particularly the subset of Finite State Machines (which AwardNotification qualifies as). Don't let the wealth of material available on the subject scare you from the usefulness of the concept. |

| [3] | This diagram was very simply created with Graphviz using the text version of the diagram that can be found in the remarks section of comments of the enum AwardNotification.State. |